There are at least three major ways that skyrocketing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are affecting the oceans and species, like humans, that depend on them; you probably already know about soaring temperatures and about rising seas, but scientists discussed the third – ocean acidification – at a roundtable panel Wednesday in Sarasota.

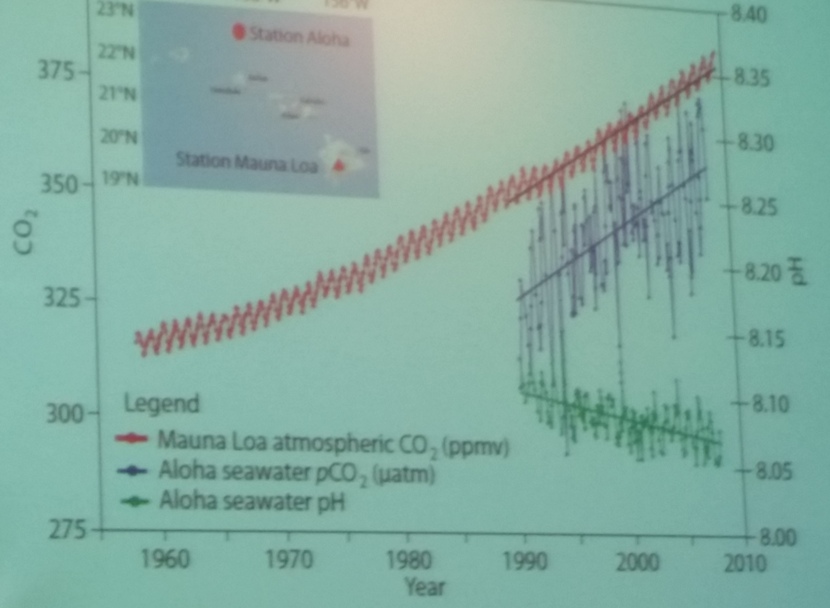

Higher concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere leads to more of that greenhouse gas getting absorbed into the oceans. Increased levels of CO2 in the seas turns them more acidic, which can be measured by declining pH levels.

Dr. Michael Crosby, president and CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory, which is hosting the panel, calls ocean acidification “probably one of the most pressing grand challenges that are facing our oceans today.” It even affects the native scallop populations that Mote and others are trying to restore in Sarasota Bay.

“Scallops have a calcium carbonate skeleton and calcium carbonate is impacted by ocean acidification. Ocean acidification is basically the lowering of the pH of the ocean water. And when that happens it makes organisms like corals, organisms like shellfish, such as scallops, have a much more difficult time in forming their shells. And they have a very difficult time in terms of carrying out their normal physiology under an increasingly acidic environment. So when we’re looking to restore the population of scallops here in Sarasota Bay we must take into consideration that the pH is falling and will continue to fall for decades to come.”

Crosby says Mote researchers are looking for genetic strains of scallops and corals that will have a better chance of survival in a more acidic ocean.

Kim Yates is a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey in St. Petersburg. She says because of Florida’s limestone geology the state could be severely impacted by ocean acidification.

“One of the interesting things about decreases in pH is that carbonates – or limestones – and lime muds dissolve as you decrease pH below a certain point. The state of Florida is a carbonate platform. Most of our underlying geologic structure is made of carbonate and our coral reefs are made of carbonates. So we’re very concerned about how ocean acidification may interact with the underlying geology and our coral reef structures.”

Chris Langdon is a professor at the University of Miami in marine biology and ecology. He has found coral reefs in the Keys have already been impacted.

“We had thought that ocean acidification was a future problem. Maybe not a serious problem until like 2050, 2060 based on some projections. But I’m finding that seasonally reefs in the Florida Keys are already starting to dissolve during winter months and that there’s a north-south trend, where the reefs to the north are dissolving more than the south. So in the south, the reefs are the healthiest. But as we get closer – it might just be closer to a population center, Miami-Dade County – but the reefs up there are seriously dissolving each year.”

Why should people care?

“A lot of reasons; they provide really important ecological services. One of them is coastline protection. You can consider it a living seawall that repairs itself from hurricane damage at no cost to us. And it can keep up with reasonable levels of sea-level rise.”

Langdon says coral reefs absorb about 90 percent of the wave energy before it hits a coastline. But he warns that in future with fewer corals more of that energy will hit coastline and destroy mangroves and seawalls.

Listen to the ocean acidification panel discussion:

https://soundcloud.com/wmnf/oceanacidification0902

Some videos of the ocean acidification panel discussion:

(original air date and publication, September 2, 2015)